Chronometers (like compasses) are highly sensitive instruments. In order to overcome the motion of a ship they need to be set in a box with gymbals, that is, in a box with some kind of contrivance made of rings and pivots which will keep the instrument horizontal at sea. One of the specialist trades that contributed to their construction was that of the ‘gymbler’ who made the boxes. Kelly’s Directories indicate that there were three specialist gymblers in London before 1897; afterwards, only two were left, namely a Miss Clarke and John Ottway & Son. After 1905, only Ottway, although there may have been other firms that supplied the service that were somehow omitted in the listings1.

The present note is prompted by the mention of ‘Ottway the gymbler’ in Gloria Clifton’s ‘New light on chronometer makers and scientific instrument trades in the nineteenth century’, in this journal’s September issue (2016: 37/3, 343). Dr Clifton’s reference described Ottway as an ‘optician and instrument maker’ and she has now helpfully added that the description of Ottway as ‘optician’ comes from ‘the Post Office London Directories … If he bothered to advertise in this way we must assume that he made, or at least sold, some kinds of optical instruments. Indeed the Heal Collection of trade cards at the British Museum has an example for John Ottway, Optician, Mathematical and Philosophical Instrument maker, No. 6, York St, Covent Garden, on which he advertised ‘Spectacles to suit all Sights’. The name ‘John Ottway’ appears in more than a dozen London addresses during the nineteenth century. After 1871 the ‘& Son’ was added. The Ottway workshop evidently made more than just ‘gymbals’ boxes for Kullberg’s chronometers for, as Dr Clifton adds, ‘between 1877 and 1914 Ottway & Son appeared in Post Office London Directories as magic lantern makers as well as opticians’2.

Ottway’s boxes were evidently of high quality for the firm also worked for at least two other leading chronometer makers. The firm supplied Usher & Cole ‘with brass work and gimballing’, (although ‘the wood boxes were practically all made by the Marshall family’)3. It also did regular outwork (‘with gymbals and fittings’) for the House of Mercer, even after it had moved to St Albans in 1872 (ostensibly to ‘escape the tyranny’ of Clerkenwell’s scattered outworkers)4.

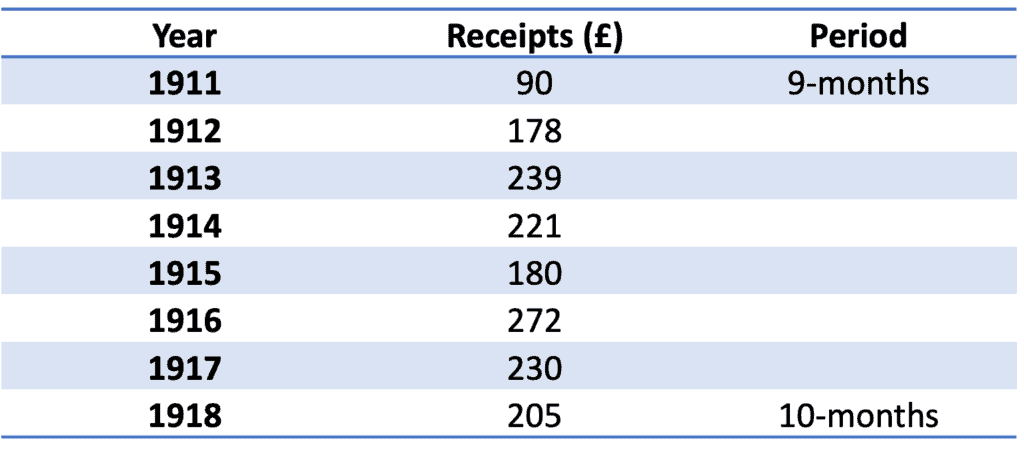

What is known about Ottway & Son is tantalisingly brief. It is mostly derived from the little Account Book in the Kullberg Archives in the Guildhall which specifies the nature and volume of the firm’s work for Kullberg between 1911 and October 19185. It shows what a fillip was given by the Great War to the demand for chronometers and thus for the special boxes into which the instrument was placed.

TABLE 1.

Annual Receipts of John Ottway, Gymbler, with House of Kullberg, c.1911- c.1918

Account book of John Ottway

These receipts show that Ottway’s business with Kullberg brought in work worth between £2 10s a week and, in the busy years of 1916 and 1917, up to £5 or £6. They don’t reveal how busy the firm may also have been for Mercer or any remaining independent chronometer ‘finisher’. To estimate the income derived from this it would be necessary to deduct the costs of materials (mahogany and felt for boxes, brass and steel for the gymbal mechanism and winder), cost and depreciation of tools, and overheads (rent, heating, lighting). We don’t know if the firm had an apprentice or extra help during busy periods; there is simply no surviving evidence. But given the other work advertised, the firm must have been more than a one-man-band.

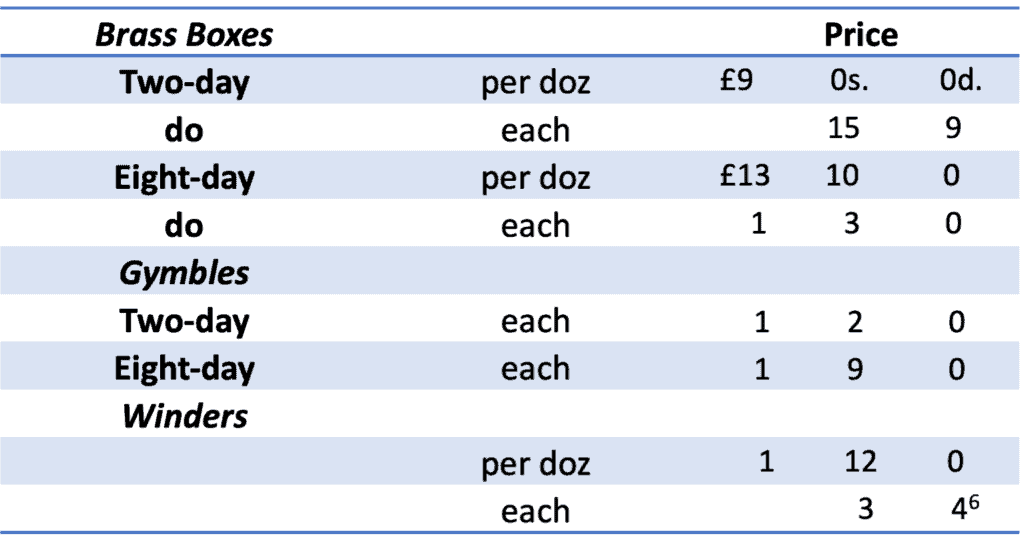

Some idea of the volume of work that the receipts represent can be gleaned from his 1917 price list for making chronometer boxes and gymbals.

TABLE 2.

Ottway’s Price List, 1917

As the sea war gathered momentum, the year 1916 was Ottway’s busiest year for business with Kullberg. Extrapolating from receipts for that year (£272) about 150 boxes – at a rate of three a week – were probably made. This is calculated from the approximations of the cost of a two day box, with gymbal and winding key (15s 9d, £1 2s, and 3s 4d.) amounting to £1 11s 1d each. Eight-day boxes, gymbals and winder cost more than a pound extra (£1 3s, £1 9s, 3s 4d), totalling £2 15s 4d. If the gymbal-making unit was small, perhaps manned by only one outworker, it is unlikely that it would make more than two or three boxes a week. Over the span of 91 months in the Order Book, aggregate receipts were £1615. It suggests that output over the long run was about 18 boxes a month and that income (receipts minus expenditure) must have been a little less than £4 a week. The price of a chronometer consisted of three elements. First was the maker’s basic cost of production, including Ottway’s boxes, as in Table 2. For example, the rough movement of Kullberg’s No. 4070 left his workshop for journeys to about fourteen different outworkers over two years: in all the cost to Kullberg of buying rough movements and paying for outworkers was £17 5s7. Next came the ‘profit’ added by the manufacturer to retailers or others in the trade: Kullberg’s normal trade price to retailers with whom he regularly did business was usually £22: this suggests a profit mark up of about 25 per cent, although it does not take into account Kullberg’s own workshop expenses. Foreign or private buyers were charged a little more – from £23 to £38, depending on whether it was a two-day or eight-day model8. Kullberg’s prices were a little higher than those of Mercer, whose basic instruments were a pound or two cheaper; from 1858 to 1902 Mercer’s price for a two day chronometer was constant at £209. Last, was the extra added by the retailer to arrive at a price to the final buyer. Prices were flexible at each stage. Regular customers often came to special arrangements amounting to discounts or rebates for large orders: details were sometimes kept secret from the end customer10.

Even the few fragments gleaned from Ottway’s Account Book add interesting and useful information. The seventeen other surviving Account Books reveal that Kullberg dealt with at least a dozen specialist outworkers; an analysis of their accounts would be a valuable contribution to our understanding of the golden era of chronometer manufacturing. Eight had addresses in and around London (for detents, springing, engraving, the gymbals, finishing, pallets, dials, and jewelling), two in Prescot (hands and movements), one each in Coventry (balance maker) and Ramsgate Kent (pivoting)11. Such a dispersal of outworkers helps to explain why the manufacture of an instrument took so long (at least a year) and why Thomas Mercer and his sons hoped that more efficiency would be achieved by centralising as much of their production as they could in St Albans.

Given the superb quality of the best of surviving instruments from that era, Ottway and his fellow outworkers made their own illustrious contributions to chronometers – including the boxes that housed them. They helped to make chronometers ‘the enduring monument of English horology’12.

1 The Post Office Directory(ies) of the Watch and Clock Trades throughout England, Scotland, and Wales, 1902, 1905, 1909, 1913, 1917, 1921. After 1917 gymbal making was taken over by the Davies, Steward Manufacturing Company, which also dealt with box turning and case making.

2 I am very grateful to Dr Clifton for helpful emails that expand on her original Ottway entry in: Gloria Clifton, Directory of British Scientific Instrument Makers, 1550-1851, (Philip Wilson, 2003), p. 205.

3 John Francis Cole and T.P. Camerer Cuss, A Watchmaking Centenary: Usher and Cole, 1861-1961, (n.p., n.d. probably 1961), p.14.

4 F.A. (Tony) Mercer, Mercer Chronometers,(1978) pp. 28 ff; [hereafter Mercer, Chronometers.]

5 Alun C. Davies, ‘The House of Kullberg’, Antiquarian Horology, 31/5 (March 2014), 635-48; [hereafter, Davies, ‘Kullberg’.]

6 3s 4d was one sixth of a Pound Sterling. Thus a dozen winding keys, if bought individually, amounted to £2. If bought ‘by the dozen’ they thus attracted a discount of 20 per cent.

7 Davies, ‘Kullberg’, 642.

8 Guildhall MS. 14,539 contains numerous examples.

9 Mercer, Chronometers, Appendix 6, pp. 155ff.

10 Guildhall MS. 14,538/2, p.195.

11 Guildhall MS. 14,553/1-18.

12 David S. Torrens, ‘Carriage clocks and chronometers’, Horological Journal, 88 (August 1946), 320-22.

Dr Alun C. Davies is a historian and author. His latest book is The Rise and Decline of England’s Watchmaking Industry, 1550–1930.