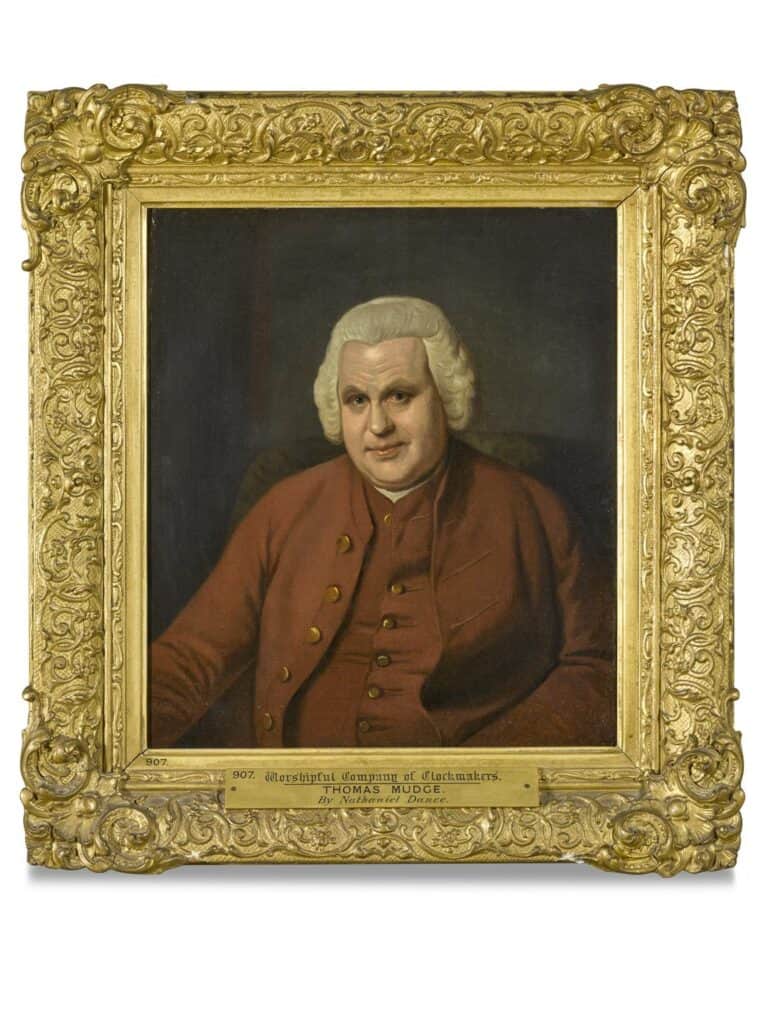

In this occasional series, we will explore the life and achievements of the greatest and most respected horologists of their time. This feature will focus on Thomas Mudge who invented the lever escapement and was appointed watchmaker to King George III in 1776.

Born in Exeter in 1715 (or possibly 1717), Thomas Mudge was the son of Zachariah Mudge, a schoolmaster and clergyman. His early education in Bideford prepared him for a life of discipline and inquiry. At just 15, he was apprenticed to George Graham, the eminent watchmaker and successor to Thomas Tompion. This was no ordinary tutelage—it placed Mudge at the epicenter of English horology during its golden age.

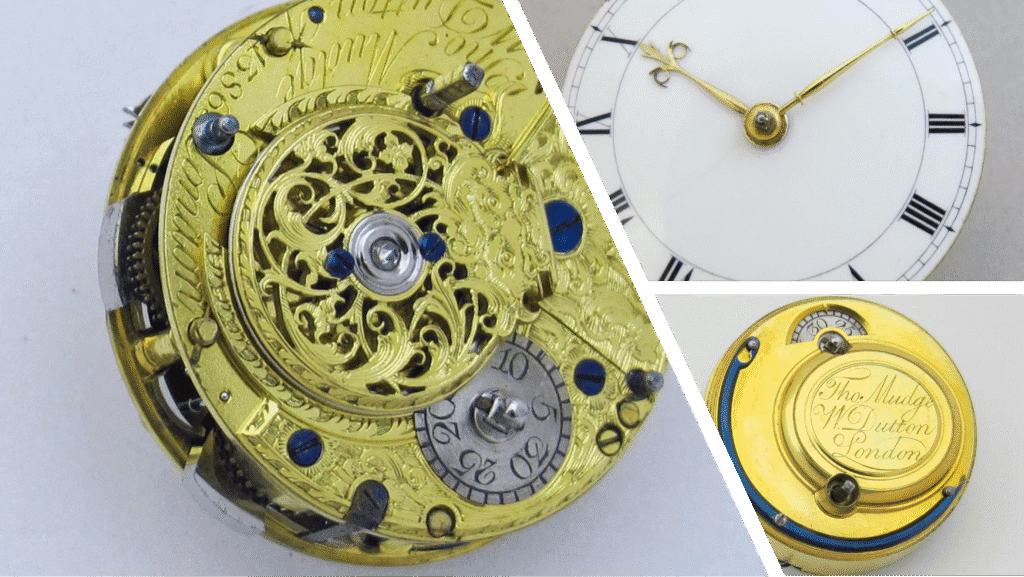

By 1738, Mudge had qualified as a watchmaker and began producing timepieces of such refinement that he was soon commissioned by Ferdinand VI of Spain. His reputation soared. In 1750, he opened his own workshop on Fleet Street, and by the early 1760s, he had partnered with William Dutton, producing watches under the name Mudge & Dutton—a mark now revered by collectors.

In 1754, Mudge invented the detached lever escapement, a mechanism that would become the backbone of virtually every mechanical watch for the next two centuries. Unlike earlier escapements, which caused friction and wear by maintaining constant contact with the balance wheel, Mudge’s design allowed the balance to swing freely for most of its cycle. This reduced friction, improved accuracy, and extended the life of the movement.

Though he first applied it to a clock, it wasn’t until 1770 that he incorporated the escapement into a watch—one purchased by King George III and gifted to Queen Charlotte.

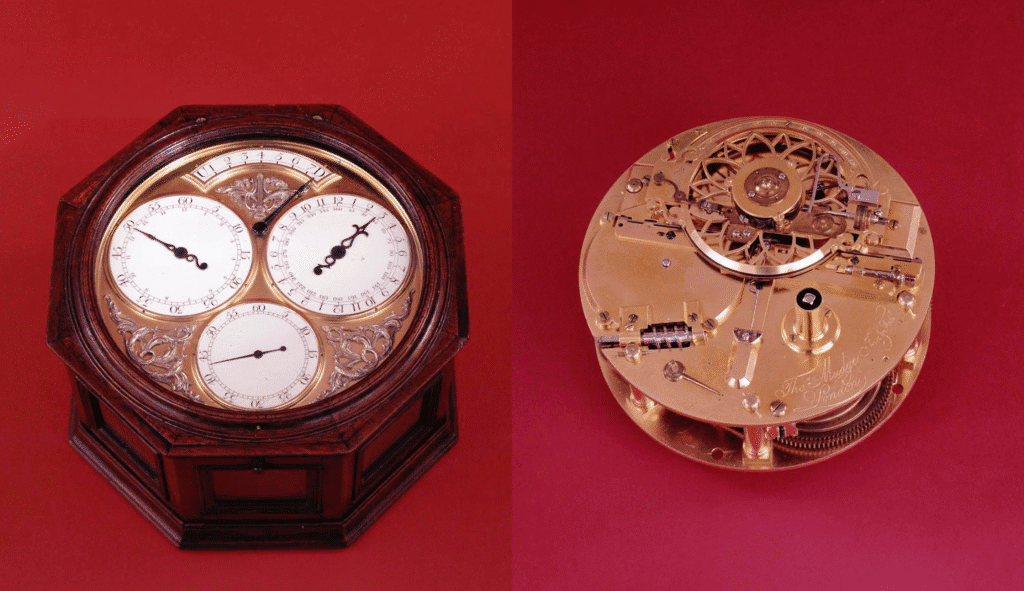

After retiring from business in 1771 due to ill health, Mudge turned his attention to the sea. Inspired by John Harrison’s work, he sought to create a marine chronometer that could determine longitude with precision. His first design, submitted in 1774, earned him 500 guineas. But subsequent trials—particularly those overseen by Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne—led to controversy. Mudge’s chronometers were declared unsatisfactory, sparking a public dispute over fairness and scientific bias.

Eventually, in 1792, a House of Commons committee ruled in Mudge’s favour, awarding him £2,500 (equivalent to £320,000 today) and vindicating his work. Though his chronometers were never mass-produced, their design influenced future generations of marine timekeepers.

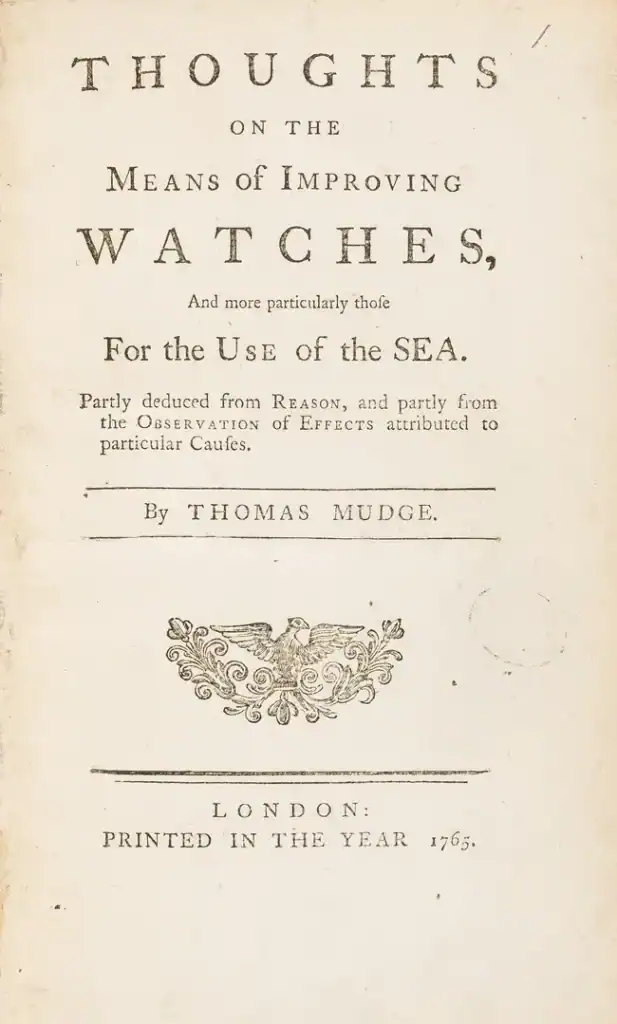

The Lever Escapement remains the most enduring innovation in watchmaking. Its principles are still found in modern mechanical watches, including the Swiss lever escapement. Mudge’s marine chronometers, though not commercially dominant, helped refine the standards by which precision timekeeping was judged. His book, Thoughts on the Means of Improving Watches from 1765 (below), became a foundational text in horological theory. As Royal watchmaker, Mudge’s name became synonymous with excellence.

He died in 1794 at the home of his son in Newington Butts, London, and was buried at St Dunstan-in-the-West, Fleet Street—a fitting resting place for a man who gave the world its most faithful measure of time.

Hero image: Portrait of Thomas Mudge (c.1715 – 1794) after Nathaniel Dance, 1770-1775. The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce © The Clockmakers’ Charity