In this occasional series, we will explore the life and achievements of the greatest and most respected horologists of their time. This feature will focus on George Graham who invented the cylinder escapement for watches, mercury pendulum and greatly improved the dead-beat escapement mechanism for clocks.

George Graham was a clockmaker, geophysicist and inventor. He invented many valuable astronomical instruments and made the great mural quadrant at Greenwich Observatory for Edmond Halley. He became a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in 1695 and was elected its Master in 1722.

Early Life and Education

George was born in in Cumberland, England, likely in the parish of Kirklinton. He was was born into a Quaker family, which influenced his values and connections later in life. Not much is documented about his formal education, but he showed an early aptitude for mechanics and mathematics, which led him toward the horological trade.

Around 1688, Graham moved to London and was apprenticed to Henry Aske, a Quaker watchmaker. After completing his apprenticeship, he joined the workshop of Thomas Tompion, the most famous English clockmaker of the time. Tompion was highly influential in Graham’s development. Graham eventually married Tompion’s niece, and the two men worked closely together for years. After Tompion’s death in 1713, Graham took over his business in Fleet Street, London.

This longcase clock by George Graham, London c.1750 has a mahogany case with printed equation table within the trunk door. The 12 inch brass dial has a matted centre, four spandrels in each corner, a date aperture, an applied silvered chapter-ring, and a subsidiary seconds dial. Signed ‘Geo. Graham London’ at the base of the dial. The movement has his famed dead-beat escapement, bolt-and-shutter maintaining power, and a flat iron pendulum rod with heavy brass-cased bob. The case, movement and winding key are numbered ‘779’. Eight day duration.

Career Highlights

Graham quickly built a reputation for precision and innovation in horology. By the early 1700s, he was supplying scientific instruments to leading scientists like Edmond Halley and Isaac Newton. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1721 due to his scientific contributions. Richard Towneley, an English astronomer and mathematician, devised the dead-beat escapement (below) for use in observatory clocks. His design was first used in a clock built by Thomas Tompion for the Greenwich Observatory. George Graham improved Towneley’s design, making it more practical and reliable for general use in precision clocks.

The deadbeat has a second face on the pallets, called the ‘locking’ face, with a curved surface concentric with the pivot that the anchor turns on. When an escape wheel tooth is resting against one of these faces, its force is directed through the pivot axis, so it gives no impulse to the pendulum (unlike the anchor escapement), allowing it to swing freely. Graham’s version became the standard in high-quality clocks for over a century due to its superior accuracy.

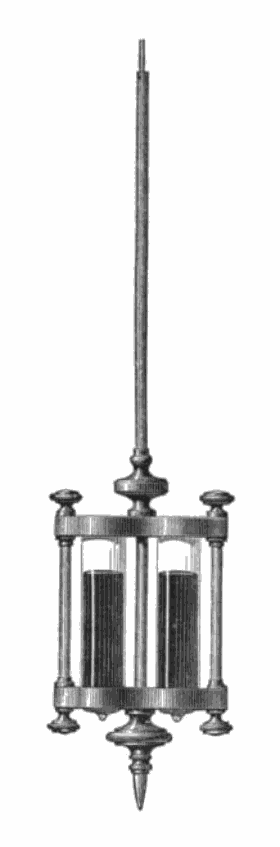

Graham invented the mercury pendulum (above) in 1720, that offered the key advantage of temperature compensation, which significantly improves a clock’s accuracy. In a traditional pendulum, the metal rod expands or contracts with temperature changes. This changes the length of the pendulum, altering the swing rate and making the clock run fast or slow. By placing mercury in a container at the bottom of the pendulum, its rising and falling level offsets the thermal expansion of the rod. This keeps the pendulum’s center of mass (and thus its effective length) constant.

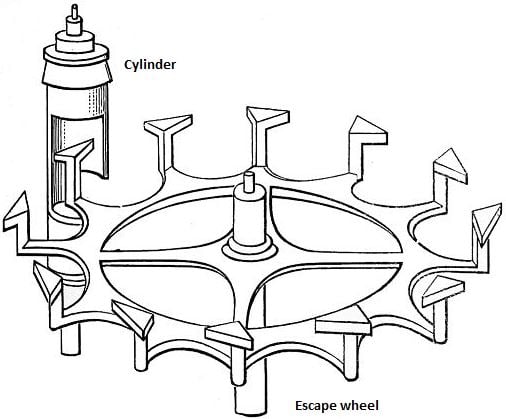

In 1726 Graham invented the cylinder escapement (above) that improved the performance and reliability of portable timepieces. It uses a hollow cylinder attached to the balance staff (the axle of the balance wheel). The escape wheel teeth enter and exit this cylinder, giving impulses to the balance wheel while allowing controlled movement of the gear train. As the balance wheel swings, the escape wheel tooth enters a notch in the cylinder wall. The tooth gives the balance wheel a push (impulse), helping it maintain motion. The tooth then escapes and the wheel waits for the next swing.

This gold pair cased watch, with quarter-repeating on bell, was made by George Graham in 1745. It has a gold inner case with pierced and engraved edges, with bell screwed to the inside. The outer case is covered with leather and studded with gold. The white enamel dial has beetle-style hands made of steel. The signed dust cap, has the number 883 scratched on the inside. The movement with repeating mechanism, cylinder escapement, is pierced and has an engraved balance cock with diamond end-stone. It is signed ‘Geo. Graham London 883’, and hallmarked for 1745–6.

The brief partnership of Tompion and Graham lasted only two years, starting in 1711, but ending soon after as a result of Tompion’s death in 1713. This watch is one of the earliest surviving from this period.

Lasting Legacy

George Graham’s lasting legacy to horology lies in his groundbreaking innovations that dramatically improved the accuracy, reliability, and scientific value of timekeeping devices in the 18th century. His work bridged the gap between early mechanical clocks and the precision instruments that laid the foundation for modern horology.

His clocks, watches and scientific instruments are still admired today in museums and collections as examples of technical brilliance and craftsmanship.

Hero Image: Oil painting portrait of George Graham, 1740-1749 by Thomas Hudson. Science Museum Group Collection © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum