Víctor Pérez-Álvarez begun as an amateur watchmaker and turned his hobby into a profession under the mentorship of Seth Kennedy and with the support of the Clockmaker’s Company.

He now works as an antiquarian watchmaker, restoring antique pocket watches. He is also a freelance consultant in antiquarian horology for museums, dealers and private collectors. We asked Víctor to share with us what a typical day involves and where his passion for watchmaking comes from.

MWM: Where does your interest in watches originate from?

VP-A: It is a long history, but one worth telling. Everything started twenty-five years ago, in the Summer before I started the Uni. I was in a Spanish town with two friends, including the priest of the local parish church, who needed help inspecting the old rectory house, which had remained closed for decades.

I still remember the moment he struggled to open the ancient door with a massive key that squeaked in the rusty lock. When he finally managed to open it, we were greeted by spiders thriving in the darkness of the house. The place was packed with all sort of objects, everything sealed with a thick layer of dust -it was a true time capsule!

Soon after we began removing items, we found issues of an ecclesiastical journal still in their original postal envelopes, bearing stamps with the effigy of King Alphonse XIII from the 1910’s. Next to them there was a box of old documents form the parish archive, the oldest dating back from the 16th Century!

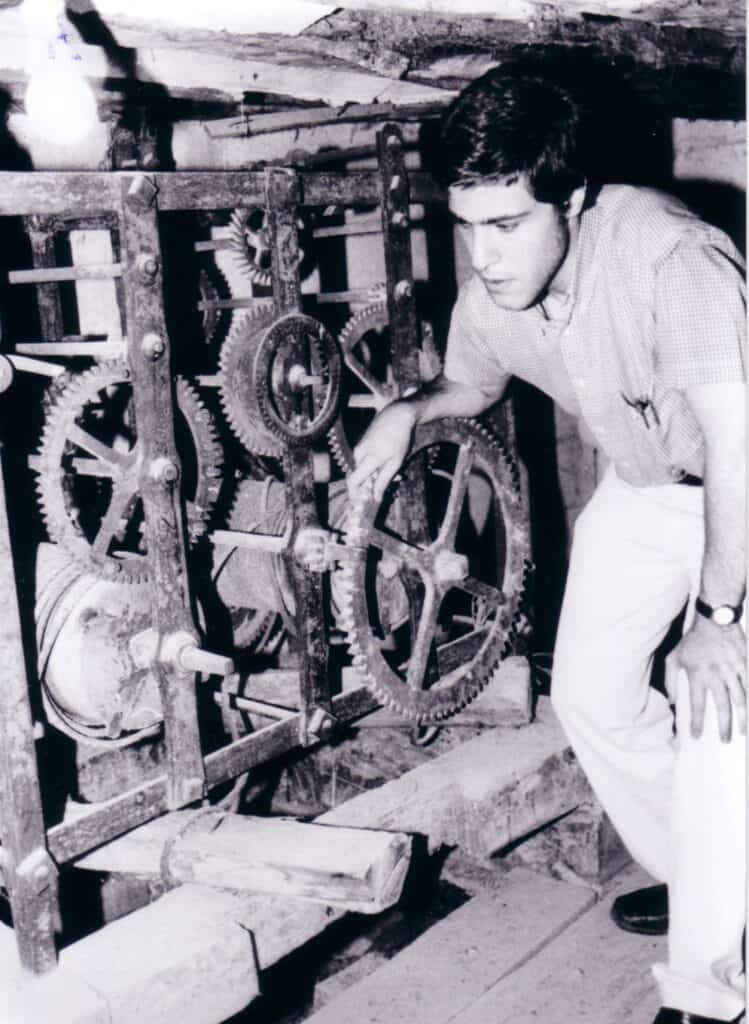

In this box, I found a bundle of papers about the construction of a turret clock for the church tower from the 1780’s. A few days later we climbed the tower and discovered a rusty turret clock movement that appeared to match the description in the old documents. You can imagine how excited that future History student was!

At that point, I had to leave to start the university but the following summer we decided to try and get the clock running. After clearing the clock room of pigeon droppings, and following the instructions of a retired turret clock maker, we cleaned the movement with petrol and applied oil to the pivots. Then we hang the weights, levelled the pendulum, and gave it its first impulse. It ticked non-stop until the weights reached the ground. We were hearing the same sound someone would have heard during the reign of King Charles III of Spain.

A Few hours later, the clock confirmed that we were, in fact, travelling back in time: the hands were rotating backwards! We later discovered that a pair of wheels in the transmission was missing.

That experience shaped my future.

MWM: How did you become watchmaker?

VP-A: Soon after the treasure trove in my town I noticed that the history of horology had been barely studied in Spain, hence I decided to pursue a Doctorate in History of Horology. I was a professional scholar by that time but I have always been interested on objects, especially on living historical dynamic objects as vehicles that connect you with people from the past. By then, I was bringing back to life antique valve radios from the 1920’s and 30’s as a hobby. I had always felt curious about clocks and watches but considered them too difficult. However, one day I decided to give them a try: I bought a basic set of watchmaking tools – tweezers, screwdrivers, hands levers, etc – and a job lot of scrap wrist watches. No pivot survived to my first watchmaking experience! Then I bought more and more watches to practice and eventually I got one of them running, a cheap post war English pin lever which I still keep and use occasionally.

A few years later, after finishing my thesis in Spain, I moved to London to carry out a research project on a 16th Century clock from the National Maritime Museum of Greenwich. I decided to move here for good and brought my watchmaking tool set with me, initially with no intention of becoming a professional watchmaker. However, here in the UK I had easier access to technical texts and to the fantastic community of the AHS (Antiquarian Horological Society), which fed my interest in practical watchmaking. This is where I met Seth Kennedy, a well-respected antiquarian pocket watch and case maker who offered to help professionalise my skills. That’s how I officially started my watchmaking career. More recently, The Clockmakers Company, patronised my apprenticeship, boosting my learning process.

MWM: What are you currently working on?

VP-A: Currently, I am restoring two continental repeaters from the 18th and 19th centuries. The earlier one is full-plate, which makes it more challenging to work on, especially when assembling all the tiny repeating wheels between the plates.

The later watch is easier to reassembly and has several interesting features, such as a relatively early cylinder escapement and a Breguet-style parachute on the balance top pivot. It is jewelled up to the centre wheel, and every single part is finished to a very high standard.

I still do scholarly work – I love researching, discovering unknown things and publishing them. Currently, I am working on Bells of time, wheels of pride: A history of the mechanical clock in Spain, the English version of my second monograph, which will hopefully see the light very soon.

MWM: Typically, what does your working day involve?

VP-A: After about an hour’s trip, we arrive at our happy place. We then plan the tasks and goals for the day and get straight to work, that’s it! The workshop is part of a heritage centre that also houses other artisans practicing rare traditional crafts. Sometimes there are visitor tours, which are fantastic opportunities to engage with people, to explain some of the intricacies of watchmaking, and to spark interest, especially among the youngest.

When it comes to scholarly work, I sometimes work from home, and sometimes from libraries in Central London, including the Guildhall and the British Library. I also travel occasionally to consult historical documents in archives or examine objects in museum collections.

MWM: What do you enjoy most about your work as a watchmaker?

VP-A: This is a fantastic job in many aspects. You often work on rare and valuable watches that very few people get to see, other than their owners. In these situations, you face new challenges, which are invaluable opportunities to learn. Sometimes, customers pop into the workshop with their family heirloom – an old watch – that has sat at the bottom of a drawer for decades. This type of customer isn’t necessarily interested in horology, but they have a strong emotional connection with the object. Seeing their faces when you deliver their fully restored watches is incredibly rewarding!

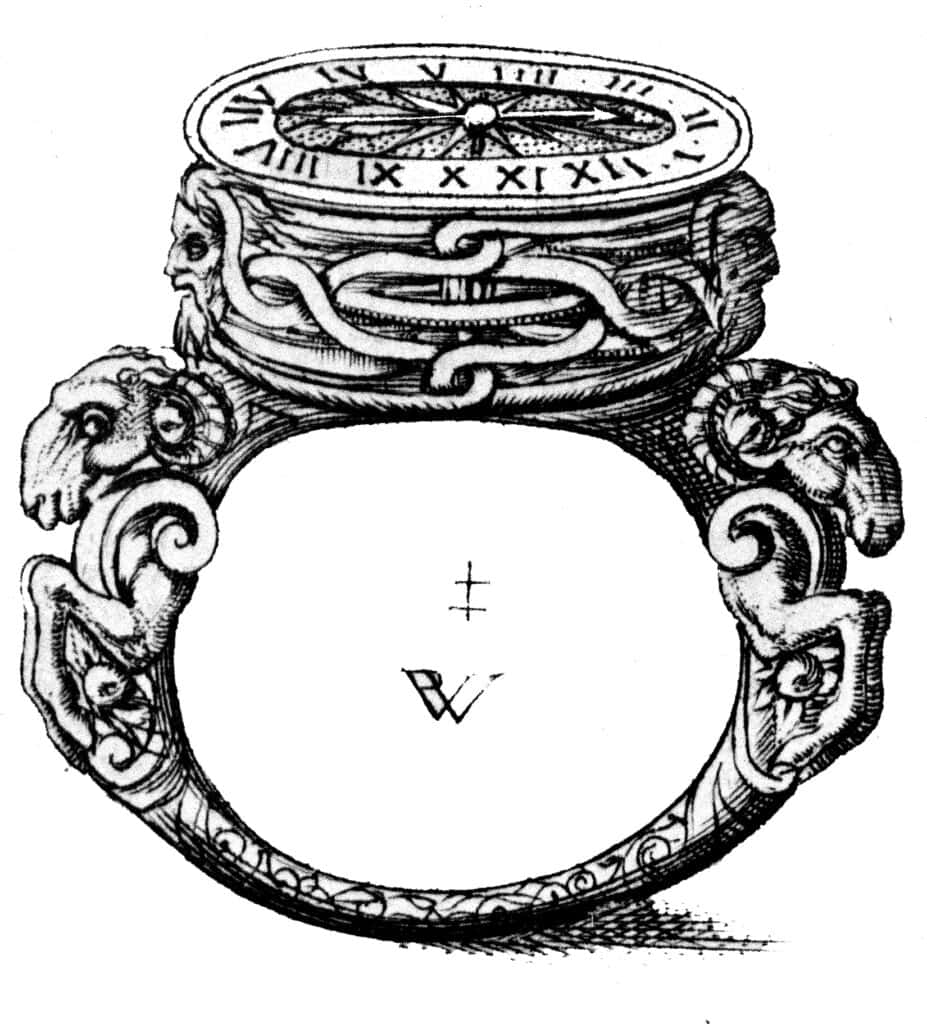

As a historian, it’s always gratifying to publish something and have people read it. However, there are no words to describe the feeling of discovering unknown documents in archives. One of my most remarkable findings was a set of original letters from the 1530’s about Emperor Charles V finger-ring watch – the tinniest watch ever built at the time (similar to the above). The movement had stopped, and no one in the Imperial court could fix it, so the Emperor decided to use his diplomatic network to find its original maker. He eventually discovered that the watchmaker had been jailed in Venice, and his ambassador had to formally request the Doge to release him so he could repair the watch. Isn’t that an amazing story?

MWM: What are the most difficult aspects of being a watchmaker?

VP-A: When you’re enjoying something and want more, the hardest thing can be knowing when to stop! However, in watchmaking, that ability is essential. We are human, we get tired after working for a long time, and pushing yourself too far can be risky for the watch you are repairing. Many people think horology, especially watchmaking, is technically difficult to learn because of the scale involved. That’s exactly what I thought at first. But, in my experience, it’s all about practice, and practicing under the guidance of a proper master.

MWM: If you had to choose a favourite watch you’ve worked on, which one would it be?

VP-A: I couldn’t choose just one. Watches are ‘very human’ machines, each has its own personality, which makes It especial. Among my favourite watches I’ve ever worked on is a single-hand French ‘oignon’from around 1690, in remarkably good condition. It is amazing to see something that is still working after more than 300 years!

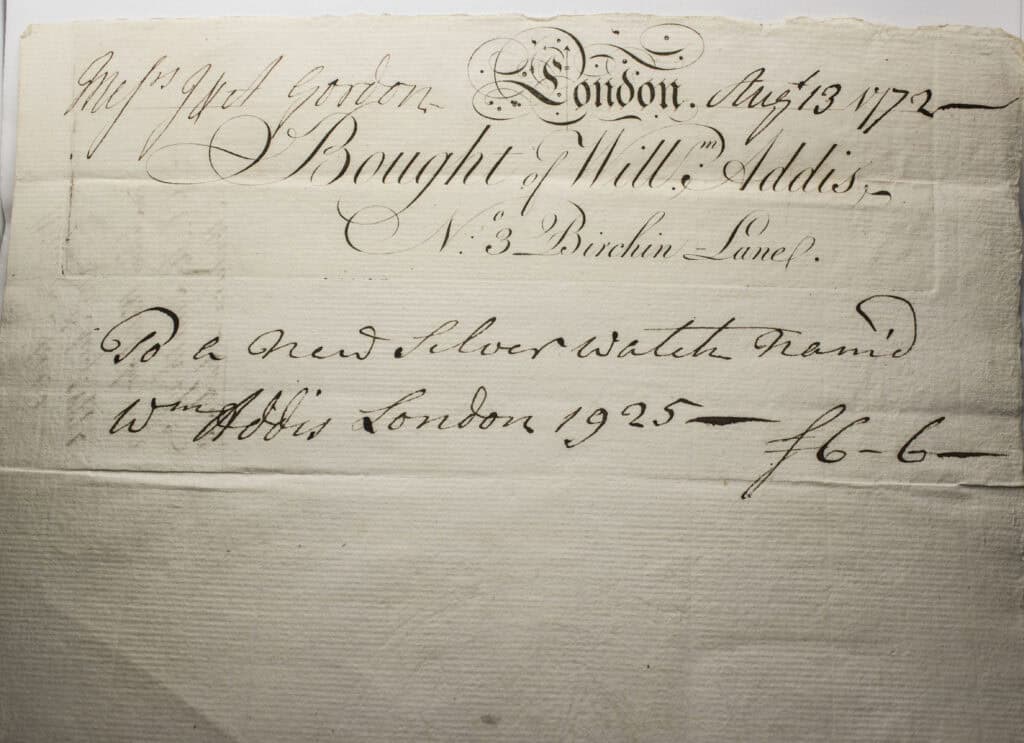

One of my favourite pieces in my personal collection is an English verge watch from the 1770’s, signed by William Addis (above), a past master of the Clockmakers’ Company. The watch features an off-set sub-seconds dial with the hand on the contrate wheel arbor. At first glance I thought it could be an early cylinder, but it turned out to be a verge. The craftmanship is superb, and includes other unusual features, such as escape wheel with 17 teeth. The object is a testament of the top end of the English watchmaking industry. I also have an original invoice from William Addis for a similar watch from the same period (below)!

MWM: What would be your advice to anyone who wanted to become a watchmaker?

VP-A: Watchmaking is a fantastic job, it sharpens your attention to detail, mechanical thinking and concentration skills. Be patient, take your time and don’t take shortcuts or you will regret it. If, at the end of the day, something seems unsolvable and you feel stuck, set it aside, grab a pint from your local pub, and the next day, with fresh eyes, the solution will often reveal itself.

Appreciate the good things about your work and be passionate about it.

For more information please visit Dr Timepiece

Víctor Pérez-Álvarez is a Friend of MrWatchMaster